© Ross Edwards 2015

Peter Sculthorpe 1929–2014: Ross Edwards speaking at the Peter Sculthorpe Celebration Concert, 25 October 2014

My first meeting with Peter happened soon after he became a lecturer in the Music Department of Sydney University where Anne Boyd and I were first year students. Quite spontaneously, it seemed, the three of us entered into a friendship which lasted 51 years. Peter’s gentle charisma had an exciting edge to it, and it soon became clear that he intended to break out of the insignificant box designated for Australian music. To this end, he cultivated an image which included a casually debonair dress sense and a red two-seater sports car. Anne always got to sit in the passenger seat while I’d curl up on a sort of ledge at the back. This was long before seat belts and Peter was a pretty zappy driver, but he exuded confidence and we soon learnt to trust his judgement implicitly, whether musical or otherwise.

Peter was a true gentleman. He was courteous, kind, tolerant, with an easy manner in his dealings with people from all levels of society. Fortunately these benign qualities were relieved from time to time by a streak of mischief that led to bursts of spectacular behaviour bordering on the scandalous. He loved to make extravagant public statements, as when he announced to the 1960s press that Europe was dead and that Australia, Asia and the Pacific were the future – this towards the end of the notorious White Australia Policy, which alienated us from a large part of our region. Peter’s comments were aimed squarely at the “cultural cringe”, that crippling manifestation of inferiority complex which had to be disposed of if we were to have a musical life that truly reflected our landscape, society and the need for cultural and geopolitical re-thinking. This bravado, supported enthusiastically by Professor Donald Peart, sparked an interest in ethnomusicology in the Music Department of Sydney University, whose focus had hitherto been obediently Eurocentric. As a result Barry Conyngham chose to do postgraduate study with Toru Takemitsu, Peter’s equivalent in Japan, who, in fusing his country’s traditional music with recent European trends, had developed a fresh voice that spoke directly to Japanese audiences. Anne Boyd and I, although we spent our postgraduate years in Europe, were drawn back to Australia – as earlier generations sometimes were not – because we sensed that something was going to happen here and we wanted to make our contribution. Apart from that, it was our home.

Less public but equally galvanising declarations were made by Peter around his kitchen table with his students listening enthralled. We learnt, for example, that he’d once made love to Elizabeth Taylor in her lavish hotel suite while her current husband had gone out to buy cigarettes. This is such stuff as myths are made on. Sceptical we may have been, but we were prepared at some level to suspend disbelief because we needed stories that embodied daring, virility and fertility – our own versions of Prometheus snatching fire from the gods or Zeus’s seductions of mortal women. Always presented in an airy “as you do” manner, Peter’s tall stories, I’m convinced, were calculated to have a life beyond their first, predictable, impact. Perceiving this, my wife once said to him: “Peter, you’re such a clever man”. He just smiled and said “I know”.

Looking back on the music he produced during the 1960s I can see further evidence of a ground plan to sustain his own work and with it Australia’s musical future. Each piece he produced was individual, meticulously crafted and at the same time, eminently practical – a strong, direct statement with extra musical associations which audiences could relate to. The titles, too, were succinct and memorable. I was working for Peter at a time when he was composing a seminal new orchestral piece to represent Australia at the 1965 Commonwealth Festival in London, and I remember discussing with him what it should be called. In the end he chose a title that has sunk into our consciousness – Sun Music – and the cover of the published score had a simple but arresting sun image by his friend Russell Drysdale.

In the late 1960s and early 70s Peter began to explore the music of our Asian neighbours, whose influence can be heard in such landmark works as Sun Music III and Mangrove. Then, gradually his attention shifted back to the Australian landscape, especially the outback. Ecstatic flights of birds, earth-based drones and melodic lines resembling the contours of Aboriginal chant appeared in his music at this time, culminating in such works as Kakadu – which we’re shortly to hear – and the monumental Requiem, of 2004. The Sculthorpe sound is instantly recognisable and it will stay with us.

One facet of the myth that I think should be dispelled is Peter’s largely unjustified reputation for prodigious drinking and partying, which belies the seriousness of his purpose and his extraordinary capacity for hard work. Those of us who spent time working in his house and studio will remember the serene, industrious atmosphere that prevailed and the humour that helped sustain it. We had plenty of fun, but never at the expense of meeting the highest artistic standards – as well as deadlines. Very many stories and reminiscences have been surfacing in my mind over the past few months: I have to tell you he led a much fuller life than his published autobiography would have us believe. We’ll miss him tremendously, but I’d like to emphasise how important it is now that we build on the legacy which he and other composers of his generation have given us, and continue to make music which seeks to reflect, validate and vitalise our life in this continent and help define our place in the world. As another great Australian, recently departed, might have observed: It’s time.

Ross Edwards

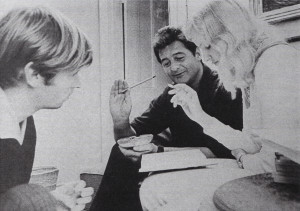

Peter Sculthorpe with Ross Edwards and Anne Boyd in Sculthorpe’s house in Queen Street, Wollahra, in 1968. Photograph: Lance Nelson.